When a golf course is being laid out largely on sandhills at the seaside, there is generally less scope for the arrangement of the holes according to the set theories of golf architecture than there is when the ground at disposal is situated inland and consists of more level and less broken country, perhaps largely of heath or moorland, or, as is very frequently the case in these days, of meadow-land. The flatter the land and more sameness there is about it, the more artificial has the course to be: and it follows from this that those who plan it can make and arrange it very much according to their own taste. But when high sandhills, large open sandpits and all the other peculiarities of the sandy wastes of some seaside places have to be dealt with, the case is different. The opportunities for laying out golf courses on such land are comparatively few ; but such courses provide the best and most interesting golf, where at the same time it is both necessary and desirable that the holes should be laid out and arranged in such lengths as are suggested by the lie of the land, every natural obstacle being taken advantage of. In such a case the object will, of course, be to approached as near as possible to the set theories of the designers of the course. I consider that in every case a good course should possess the following general features:

(1) There should be a complete variety of holes, not only as regards length, but in their character–the way in which they are bunkered, the kind of tee shot that is required at them, the kind of approach and so forth.

(2) In every case the putting green should be thoroughly well guarded.

(3) The shorter the whole the smaller should be the putting green, and the more closely should it be guarded ; so that on this principle, when in good play a long shot can reach the green, that green should be fairly large and open in order to give the player the encouragement to which he is entitled.

(4) There should be alternative tees, in order that the course may be easily adapted to varying winds and dry weather, when there is more run on the ball.

(5) The bunkering and general planning of the holes should be carried out with the specific object of making it necessary not only to get a certain length, but, more particularly, to gain a desired position, and the player who does not gain this position, should have his next shot made more difficult for him, or should be obliged to take an extra shot.

(6) There should be, as frequently as possible, two alternative methods of playing a hole, an easy one and a difficult one, and there should be a probable gain of a stroke when the latter is chosen and the attempt is successful.

A course that conforms to these general principles cannot possibly be a bad one. Now, from such a general statement as this, I go on to a more particular one as to the lengths of the various holes and their arrangements. I think that in every good course there should be :

(1) Four short holes, all of different type. One of these four should be a very short one (about 120 yards) ; a second should be a little longer, so as usually to make the difference in the choice between a mashie and an iron ; a third should generally call for a cleek shot, or just a little bit more than that ; and the fourth should represent a good full drive.

(2) There should be two very long holes of fully 500yds. each or a little over, 550yds. being regarded as the maximum.

(3) The remaining holes should vary in length between about 320yds. and 420yds., those between 360yds. and 420yds., representing always good two-shot holes, predominating.

(4) There should be two stiff carries to be made from the tee in the course of the round–about 150yds. each. The predominating carry should be about 130yds. ; but in some cases it may be reduced as little as 100yds., special difficulties in the way of placing the tee shot being present at such holes.

(5) As a general rule simple cross bunkers right across the course in front of the tee should be avoided. A few of them are necessary and desirable ; but preference should generally be given to side bunkering.

(6) Except in a very limited number of cases bunkers straight across the course in front of the putting greens should be avoided and preference should be awarded to the ” bottle-neck ” system of guarding the greens, by which a very narrow opening is offered to each, the traps in front, behind and at the sides being numerous.

(7) The first nine holes and the second nine should as nearly as possible match each other in total length, in golfing quality and in general character, although it is not desirable that the order of the length and variety should be the same.

(8) There should be either two or three–three for choice–holes of good but not extreme length at the beginning of the round, in order to get the players well away without a block on busy days. These should be followed by one of the short holes.

(9) The last two holes, or three, should all be of a good length, in order to induce a good finish to a well-contested match, and particular care should be taken to see that the seventeenth and eighteenth holes are a thorough test. A short hole for the last one is to be avoided if it can be, increasing the possibility of winning by a fluke ( if it cannot be avoided it must be made extremely difficult ). The hole should generally be of a full two-shot length, and the green should be thoroughly well guarded.

(10) The total length of the course should be between 6,000yds. and 6,400yds.

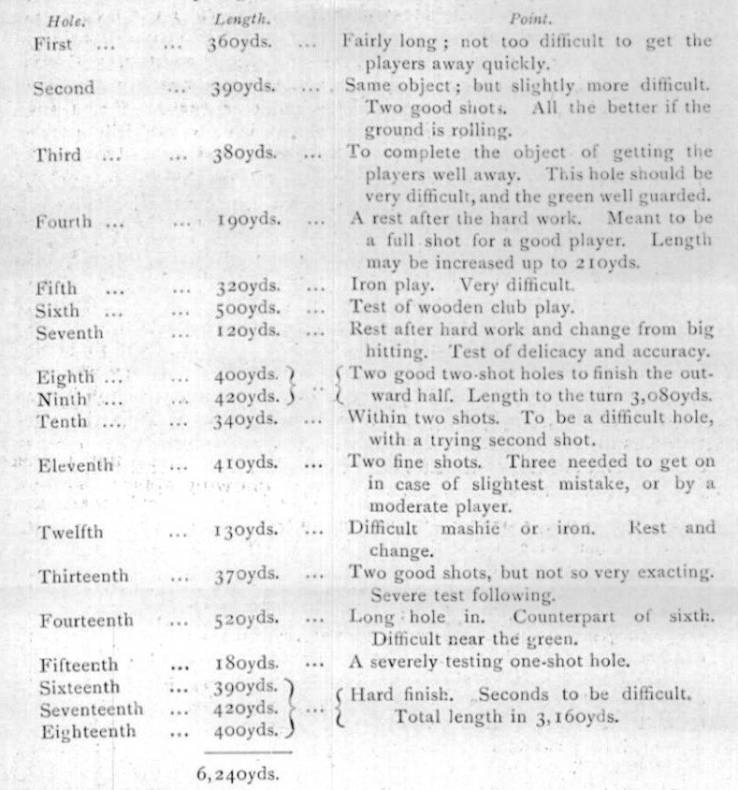

I will now set forth the lengths of the holes and the order of their arrangement, and the chief point, quality or character of each, on what we may regard as an ideal course of eighteen holes :

There should be short tees, in order to reduce the length of the course somewhat in winter-time. This table very nearly explains everything, and as in another article I shall have some general remarks to offer on making teeing grounds and bunkers, I will only state here what I consider to be desirable features of particular holes arranged on such a definite system as this.

The first hole should be as open as possible from the tee. There should be no difficult bunker or other hazard in the way to discourage the player at the beginning of his round and very often spoil it for him, as the result of a bad shot which is very often made under exceptionally circumstances–a long wait at the tee, a crowd on it and the player never at his best right at the beginning.

To ensure a fairly easy start there should be two or three alternative tees, some distance apart from each other, for use according to the wind that may be blowing. Also, the wear and tear of the first tee is greater than on any other. You may give the man a carry to make at the second hole, but it should not be too difficult ; and both here and at the third it must be remembered that holes of this length demand alternative tees, or they may be completely spoiled by a change of wind. At the long holes–the sixth and fourteenth–the bunkering until the green is reached should not at all be heavy. A little side bunkering and plenty of pots near the green will be quite sufficient, so long as traps are laid to catch a topped and long-running ball. The governing consideration in the case of these long holes is that the player must get length, and if he misses a shot, or goes very far off line, he has a very small chance of getting to the green in the number of strokes that he would otherwise expect to do. It should also be made that his next shot is always more difficult if he deviates to the least extent from the straight.

There should be the greatest variety in the short holes. If possible, non of them should be blind, though a blind hole may still be good sometimes. The best kind of short hole is the opposite to the blind one–that is, one where the tee is on higher ground than the putting green, and the player is able to look down on the latter, with a full view of all the difficulties that surround it. In the case of the shortest of the four holes I would have no cross bunker, or, indeed, any bunker right in front of the middle of the green ; but I would put pot bunkers all round it, and have them right up to the edge of the green, which would also be a very small one. Thus the opening to the green would be a very narrow one, demanding a most accurately placed pitch and the player would need to exercise complete control over the run of his ball after it had pitched. It is a good thing to make a green like this pear-shaped, with, of course, the narrow end nearer the tee. To insist that a pitch shot shall be played and that the player shall have no chance of getting off with a possibly fluky half-topped pitch and run I would have the fairway very rough up to within 10yds. of the putting green. The short hole which is only a little longer than this one may be constructed on the same general principles, and should be nearly, but not quite, as closely guarded and there might be a cross bunker–sunk, not raised–some 15 yards, in front of the green. The 180yds. hole will be generally regarded as a cleek shot and calling for one that is perfectly straight and well-judged. Side bunkering and a narrow opening to the green will be best in this case, and there may be something to carry at 150 yards from the tee. In the case of the longest of the short holes I would have a slightly-raised cross bunker, and I would place it diagonally to the straight line of play, giving an easy carry to the moderate player, but demanding from him that if he takes that line he must play wide and then make a short approach to the green, whereas the man who goes straight will have a long carry, but will get there if he does it.

I shall explain this system of making use of the diagonal bunker in the next article.

Although the concluding holes must be difficult, I would not give a long carry from the tee at the last one, but would bunker it so that the player would be punished for the least deviation from the straight line.

I might say a word about the par and bogey calculations for such a course as that I believe I have been speaking of. The difference between par and bogey is, of course, that the former represents perfect play and the other stands for good play with a little margin here and there. Although it is said that “bogey never makes a mistake,” It is evident that bogey does give a chance now and then, which par does not. In order that the real value of the holes may be defined I think that it would be well to reckon that value in par figures.

There is generally no doubt about the difference between 3’s and 4’s but the question is as to how you shall separate the 4’s and 5s. There should not be such a thing as a par 6. In a general way I would make holes of 390yds. and over 5’s and under that distance 4’s, that is, when they are over 3’s. The longest of the short holes, must, of course, still be a 3, though it may be a bogey 4. In distinguishing the 4’s and the 5’s, however, it is well to remember that length is not everything, and that a hole of 385yds. or 390yds. may be easier at which to get a 4 than another hole of 360yds. Questions of uphill and downhill and the bunkering about the green need to be considered, and some judgement exercised in fixing the values. I would place the par values of the holes on the course I have been writing about as follows : 4, 5, 4, 3, 4, 5, 3, 5, 5–out, 38 ; 4, 5, 3, 4, 5, 3, 5, 5, 5, –in, 39 : total 77. A par score of this kind, however, is only for players’ own knowledge and satisfaction, it is too severe for bogey competitions. One fixed and unalterable bogey score is not generally a good thing, because in certain winds quite a large proportion of the holes may have wrong values attached to them–that is to say, with the wind they may all be too easy, and against it all too difficult. It is then a simple thing, and a very satisfactory one, to have two bogeys for a course for the purpose of competition, and to decide which of them shall be in force on the morning of the competition. One bogey would be set out for one wind and another for another. For example, If the wind was against the player at the first hole (360yds.), and with him on his return journey at the thirteenth (same length), you would make the former a bogey 5 and the latter a bogey 4, and reverse the figures if the wind were in the opposite direction. For bogey I would give 5’s for everything between 370yds. and 450 yds., and after that six might be allowed. The general bogey (with variations according to wind, as I have suggested) of the course we have been considering might be placed as follows ; 5, 5, 5, 3, 4, 6, 3, 5, 5–total out, 41 ; 4, 5, 3, 5, 6, 3, 5, 5, 5–total in 41 ; grand total, 82. It is well, for reasons already suggested, to make the bogey for the first hole easy ; but there is no reason why it should be easy at the end. However carefully the bogey score of the course is arranged and even when two bogeys are made, it is seldom that there is complete satisfaction with the figures given to every hole. A 5 is often too much when a 4 is too little–that is to say, such a hole is an easy 5 but difficult 4, and it will often fail to distinguish between good play and bad. What seems to be wanted is a reckoning of half-strokes and though you cannot play such halves, a stroke being a whole stroke or none at all, there does not seem to be any reason why bogey should not be considerably improved by letting it have half-strokes. To take a case: in normal conditions of wind and weather you might make the longest of those four short holes a 3 and a 1/2, and holes of about 360yds. to 380yds. might be set at 4 and a 1/2. This would mean in the former case that the man who got his 3–and it would be generally a good 3–would win the hole, while the man who took 4 would lose it, as he would very likely deserve to do, because almost everyone could play such a hole in 4. Even this, however, leaves a little to be desired, because at these holes it removes the chance of halves being made, when halves would often represent just the value of the play. This difficulty can be got over by allowing halves in the handicap, and seeing that they are given at the right holes. for example, at the 3 1/2 hole we have just been speaking of, we might allow the very moderate player half a stroke instead of either nine at all or a full one. The result would be that if he played this hole out in four strokes, which would generally be the best he could do, he would halve it with a bogey. He would hardly deserve to win it in any case. This system of halves is much simpler than it may appear at first glance, as anybody may find out after a few minutes consideration and it certainly seems to offer a chance of making bogey a much more satisfactory and exact sort of thing than it generally is.

James Braid ~ Country Life 1908.